Introduction

Stress is often described as a mental or emotional state, but its effects reach far beyond the mind. At the center of this connection is cortisol, a hormone released by the adrenal glands in response to stress. While cortisol is essential for survival, chronic elevation can quietly reshape the body, increasing the risk of long‑term health problems. Understanding this biology is the first step toward prevention.

What Happens When You’re Stressed

When the brain perceives a threat — whether it’s a looming deadline or a physical danger — the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activates. This triggers the release of cortisol, which:

- Increases blood sugar for quick energy

- Suppresses non‑essential functions like digestion and reproduction

- Heightens alertness and focus

In short bursts, this system is protective. But when stress becomes constant, the same mechanisms can turn harmful.

Cortisol and the Body: System by System

1. Cardiovascular System

- Chronic cortisol elevation raises blood pressure.

- It promotes plaque buildup in arteries, increasing risk of heart disease and stroke.

2. Immune System

- Short‑term cortisol suppresses inflammation (helpful in acute stress).

- Long‑term exposure weakens immune defenses, making infections more likely.

3. Metabolism

- Cortisol increases glucose production.

- Over time, this contributes to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

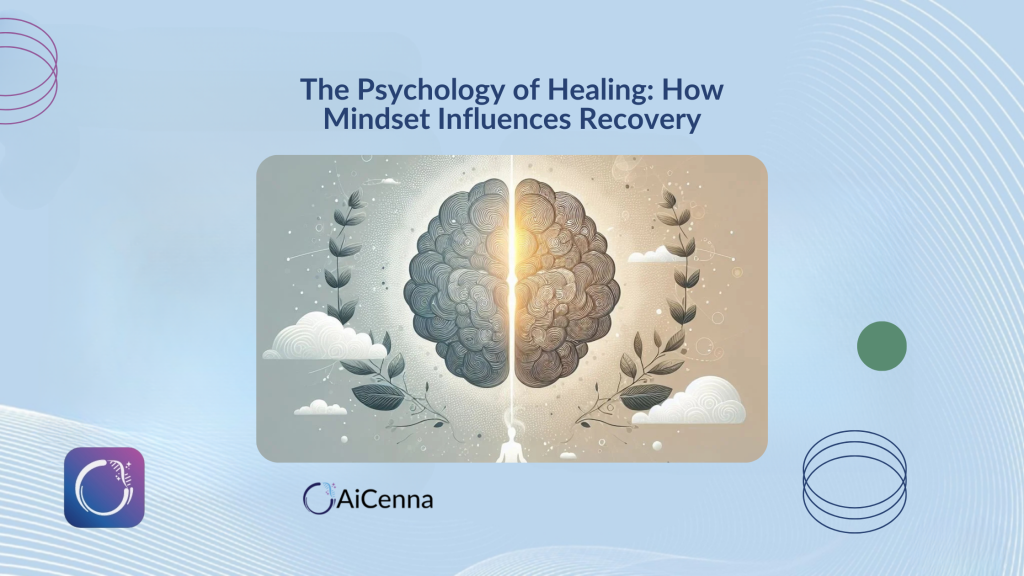

4. Brain and Mental Health

- High cortisol shrinks the hippocampus, a brain region critical for memory.

- It’s linked to anxiety, depression, and impaired decision‑making.

5. Musculoskeletal System

- Cortisol breaks down muscle tissue for energy.

- It reduces bone formation, raising osteoporosis risk.

Stress and Chronic Disease: The Evidence

- Cardiovascular disease: Studies show people with high cortisol levels are more likely to develop hypertension and coronary artery disease.

- Diabetes: Chronic stress is a recognized risk factor for metabolic syndrome.

- Mental health disorders: Elevated cortisol is consistently found in patients with depression and PTSD.

- Autoimmune conditions: Dysregulated cortisol may worsen diseases like rheumatoid arthritis.

Everyday Sources of Chronic Stress

- Workplace pressure and job insecurity

- Financial strain

- Caregiving responsibilities

- Social isolation

- Constant digital connectivity (“always on” culture)

These stressors rarely feel life‑threatening, but the body reacts as if they are.

Managing Stress: Evidence‑Based Approaches

Lifestyle Interventions

- Exercise: Regular physical activity lowers baseline cortisol.

- Sleep: Adequate rest restores HPA axis balance.

- Nutrition: Diets rich in whole foods, omega‑3s, and antioxidants reduce inflammation.

Mind‑Body Practices

- Mindfulness meditation: Shown to reduce cortisol levels in clinical trials.

- Breathing exercises: Slow, deep breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system.

- Yoga and tai chi: Combine movement with relaxation, lowering stress hormones.

Social and Psychological Support

- Strong social networks buffer the effects of stress.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) helps reframe stress responses.

The Bigger Picture

Stress is not just “in your head.” It is a biological process with measurable consequences. Cortisol, while vital in the short term, becomes a silent driver of chronic disease when left unchecked. Recognizing stress as a medical risk factor — alongside smoking, poor diet, and lack of exercise — is essential for a healthier future.

Conclusion

We cannot eliminate stress from modern life, but we can change how we respond to it. By understanding the science of cortisol and its impact on the body, individuals and healthcare systems alike can take proactive steps to reduce the burden of stress‑related disease.